Cosmology has gone through a radical transformation during the last decades; what once was a data-starved science with challenging model testing is now a data-driven precision science where there is a consensus cosmological model, ΛCDM well supported by observations. However, precision does not mean accuracy, and there are some tensions between experiments that show potential cracks in the model. Moreover, there are many unknowns to be answered yet: what is the nature of dark matter? What is driving the accelerated expansion of the late Universe? What physics drove the first instants of the Universe? Broadly speaking, I am interested in all this (and in extragalactic physics such as reionization and galaxy evolution), though of course I cannot work in all of it.

Although my research is quite broad and I always like to dip my toes in new fields and studies, my main areas of research are:

Line-Intensity Mapping Dark Matter Cosmological tensions

We only have one Universe to probe, hence the experiments in cosmology are intrinsically different than in other sciences. Therefore, it is of radical importance to exhaust the information out there, deriving new formalisms to improve the prediction of the theoretical models, statistical tools to maximize the understanding obtained from observations, as well as innovative paths to use existing observations and measurements to probe new physics. In particular, what I enjoy the most is studying novel ways to access the information that we can gather from cosmological observations.

Line-Intensity Mapping

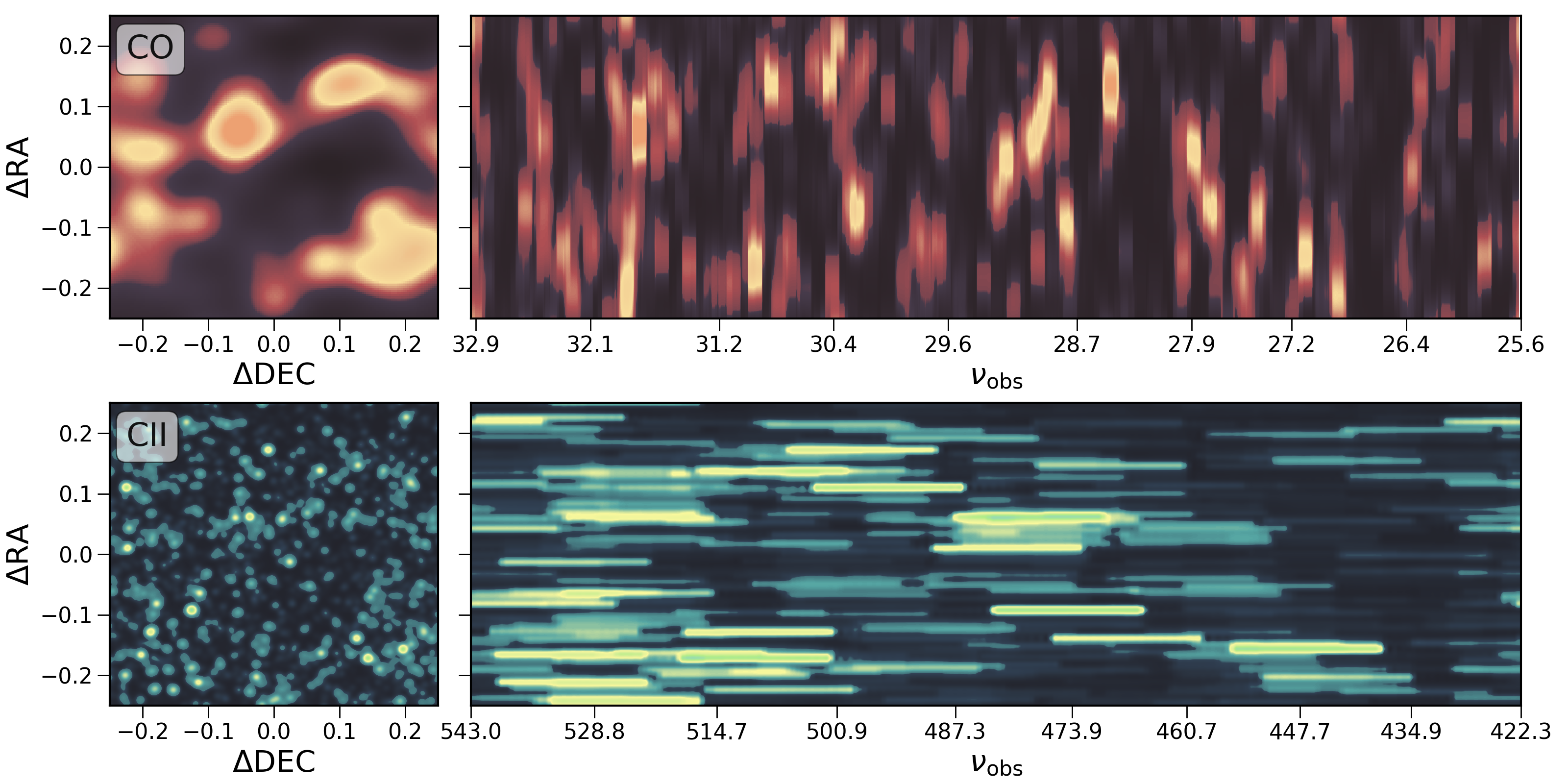

Line-intensity mapping (LIM) is a technique that employs low-aperture instruments to quickly scan the sky and collect all the incoming radiation, targetting identifiable spectral lines to recover radial information through good experimental spectral resolution. Since it does not requires to resolve individual sources, LIM provides access to redshifts well beyond the reach of galaxy surveys and is also sensitive to the population of faint sources that are hard to resolve individually. This provides direct access to epochs of the history of the Universe and regimes that are unaccessible otherwise.

Since overall fluxes are measured, LIM is both sensitive to the large-scale matter distribution and the astrophysical processes that drive the emission of each line in atomic and molecular gas clouds within and around galaxies. Thus, targetting several spectral lines provides a more complete picture of the interstellar and intergalactic media. In summary, studying intensity fluctuations with LIM promises to deepen our understanding of various questions related to galaxy formation and evolution, cosmology, and fundamental physics, while being complementary to other techniques and cosmological probes.

If you are new to LIM, maybe you want to check the recent LIM theory review I wrote with Ely Kovetz for The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review journal, focused on spectral lines related with star formation, like CO, [CII], Lyman-α, etc. There you can read about the primary target lines and the astrophysical processes that drive their emission, different approaches to model their intensities and analyze the data, the scientific prospects for the forthcoming experiments, and the synergies with other cosmological observables.

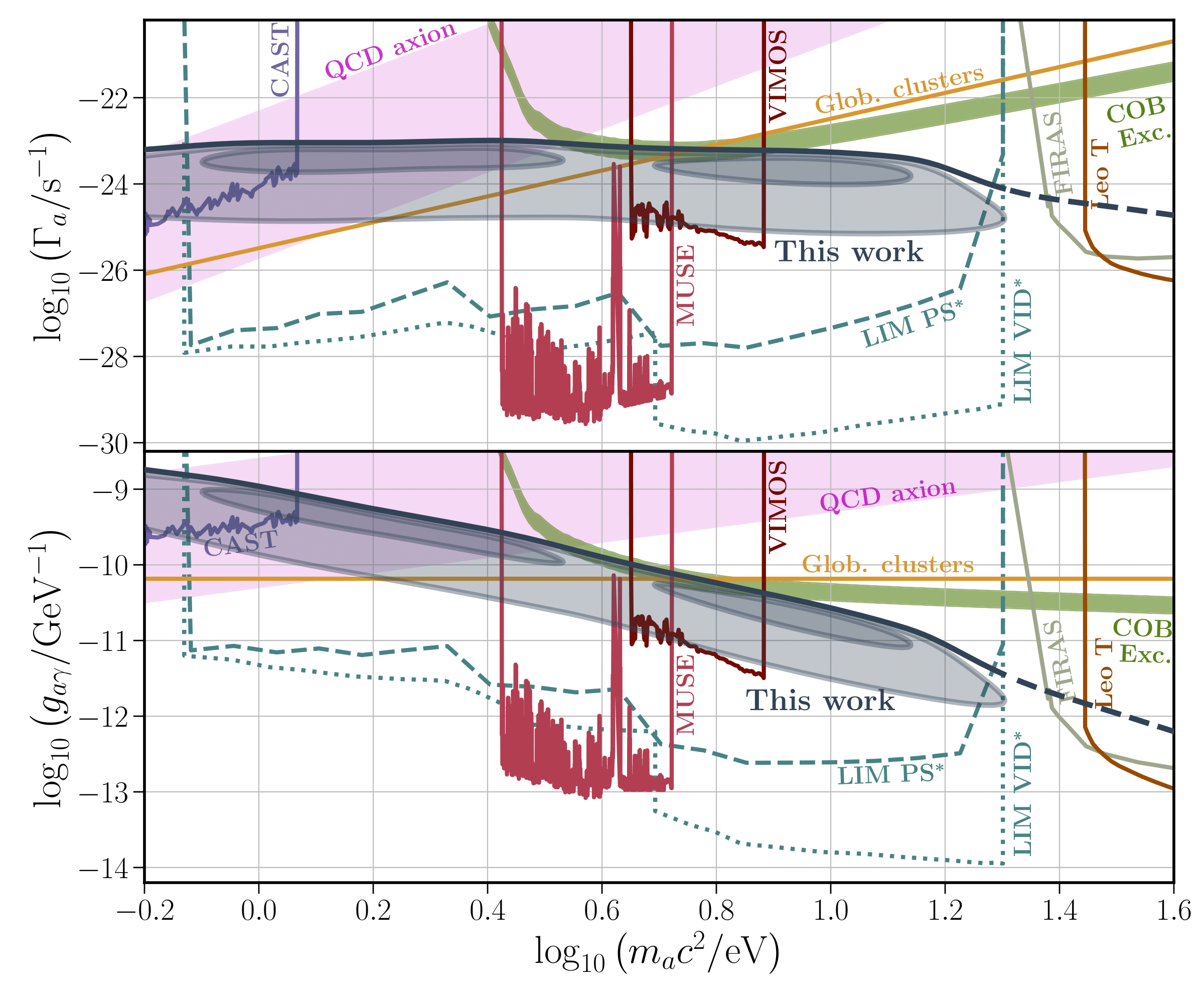

My main work in LIM has been improving the formalism to measure summary statistics from the line-intensity maps and get a theoretical prediction and the development of new science cases to employ LIM observations beyond the straightforward applications. Some examples of my work in LIM formalism include an improvement of the LIM power spectrum formalism and the derivation of the first analytic covariance between 1- and 2-point statistics of line-intensity maps (with Gabriela Sato-Polito). I have also motivated LIM surveys for probing new physics, such as the nature of dark energy extending the cosmic distance ladder to much higher redshifst, or developing strategies to detect the product of exotic radiative decays (such as dark matter or neutrinos) from line-intensity maps.

Finally, I am currently working with Gabriela Sato-Polito and Nickolas Kokron in the development of SkyLine, a flexible code to generate and analyze mock LIM observations in a lightcone, including observational effects, continuum foregrounds and contributions from line interlopers (spectral lines that redshift to the same observed frequency than the target line) and with general astrophysical halo properties inherited from UniverseMachine. More interestingly, this will be the first time that LIM mocks belong to a coherent simulated sky including a plethora of other observables, such as galaxy clustering (maps generated also within SkyLine) and CMB secondary anisotropies, cosmic infrared background, weak lensing, and radio galaxies from the catalogues from MDPL2 synthetic sky simulation by Yuuki Omori. The simulated maps shown in this page are done with SkyLine.

Related talks:

- Line-Intensity mapping: challenges and opportunities - Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) - 2022.

- Exploring the Universe with Line-Intensity Mapping - Institute of Cosmos Sciences, University of Barcelona (ICC-UB) - 2022.

- The Cosmic Expansion History from Line-Intensity Mapping - Cosmic Controversies conference, Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics, University of Chicago (KICP-UChicago) - 2019

Dark Matter

Dark matter is a key component of our understanding of the Universe presumed to interact with visible matter primarily through gravity, making up to ∼26% of the current energy density of the Universe. However, a microscopic model backed by observational and experimental evidence is yet to be found. The standard, cold dark matter is modeled as a non-relativistic, pressure-less fluid only sensitive to gravity. Nonetheless, most of existing dark matter candidates involve additional (faint) interactions with baryons. These faint interactions, of all kind of flavors, results in an extremely rich phenomenology that enables a variety of search strategies, ranging from collider searches, to ground experiments, to astrophysical and cosmological probes (either seeking directly the products of the dark matter-baryon interactions or indirect signatures of them).

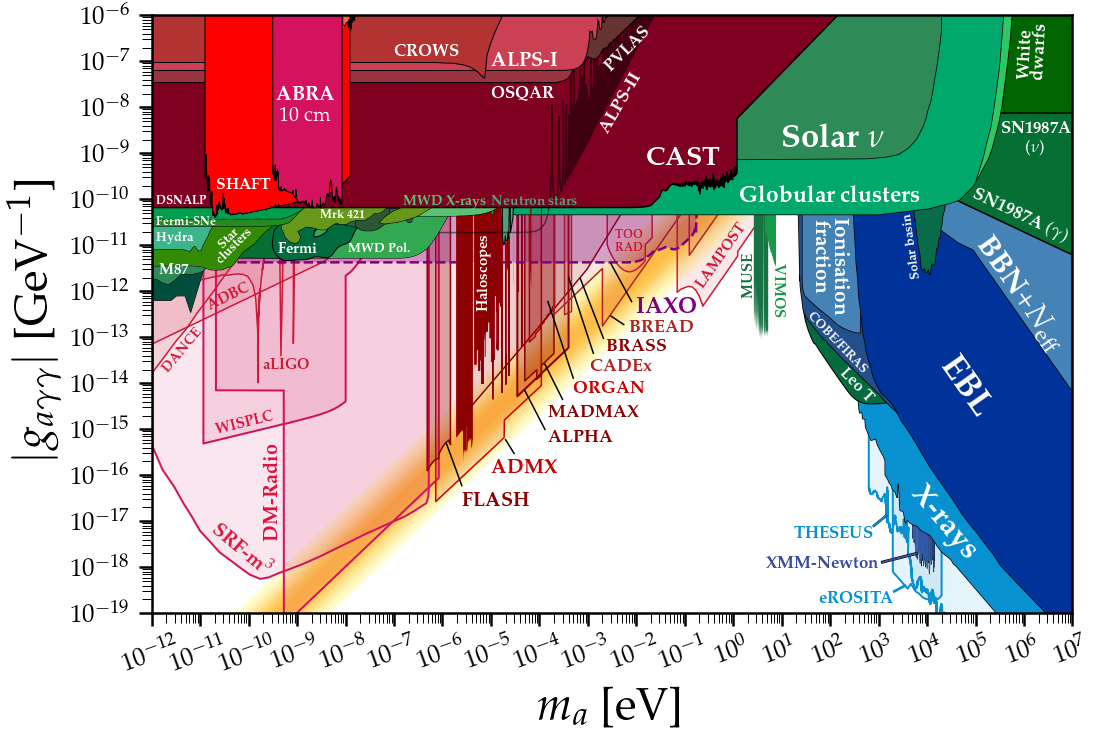

My main work in dark matter searches involves the phenomenological impact of dark matter interactions beyond gravity in astrophysical and cosmological observables, and the development of strategies to detect the signatures of such processes in the observations. The dark matter candidate I have studied the most is the axion (a particle initially proposed to solve the strong-CP problem that can also act as dark matter) and axion-like particles (ALPs). Depending on their mass, ALPs can be searched through their impact in the small-scale matter clustering, photon-axion oscillations in the presence of magnetic fields, and direct or indirect surveys of their decay into photons.

I have mostly focused on the decay of ALPs in the multielectronvolt mass range. This mass range is surprisingly hard to probe, as seen in the figure above. However, contributions from radiative decay of ALPs in this mass range may contribute to the recent 4σ excess in the cosmic optical background measured by the LORRI camera in the New Horizons spacecraft. In order to test that possibility, I have searched for contributions from these decays to the extragalactic background light in the attenuation of flux of γ-ray from distant blazars. Furthermore, I have developed novel strategies to detect the signatures from exotic radiative decays like these or neutrino decays in LIM measurements, with very promising prospects. I will continue to develop this program with other strategies.

I have also worked in other dark matter models. One example involves dark matter-baryon scattering, which suppresses matter clustering at small scale but also changes the baryon temperatures. My collaborators and I have derived for the first time the temperature perturbation equations including the contributions from this exotic scattering. We found that accounting for these effects further suppresses clustering at small scales at early times, which, together with the modified temperature perturbations, would affect the formation of the first galaxies and modify the signal of HI LIM from cosmic dawn. Finally, I have also studied primordial black holes, which could be part of the dark matter, and could also be the seeds of the supermassive black holes that are observed at very high redshifts and are too massive to be explained with standard astrophysical mechanisms.

Related talks:

- Cosmic optical background, blazars and line-intensity mapping view for multi-eV axion-like particle dark matter - Università degli Studi di Milano - 2023.

- Dark matter and neutrino decays with line-intensity mapping - FermiLab - 2021.

Cosmological tensions

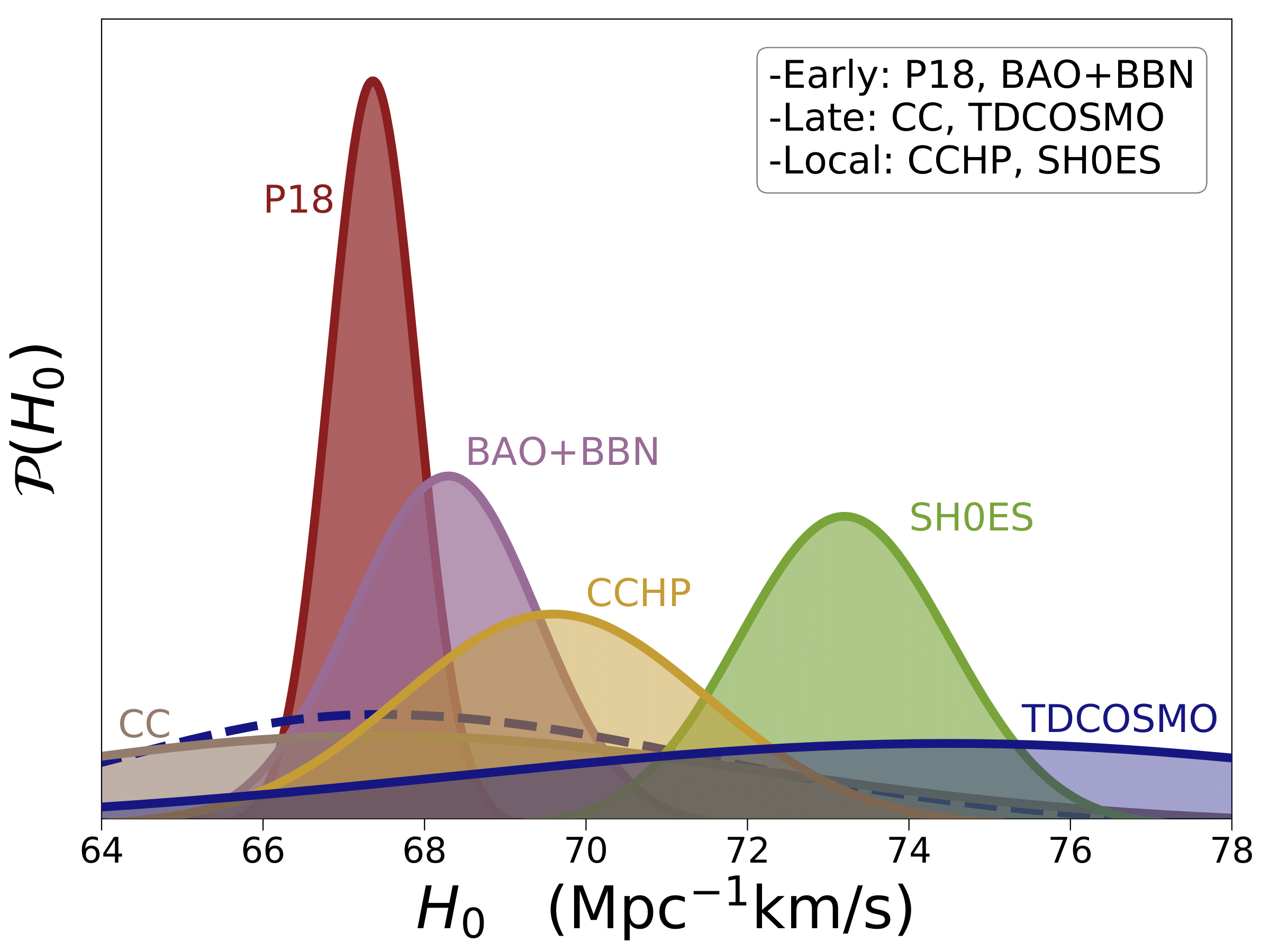

ΛCDM is a model that successfully reproduces most of the observations that we have available today, with some of its cosmological parameters constrained below the percent level precision. However, as observations, experiments and the formalism to treat and analyze the data improves and final measurements become more precise, tensions between experiments and cosmological observables have arised. In particular, the most remarkable tensions involve the Hubble constant, H0, which quantifies the current expansion rate of the Universe, and σ8 (and its combination with the matter density parameter Ωm: S8=σ8Ωm1/2), which quantifies the amplitude of the matter perturbations today smoothed over scales of 8 Mpc/h. In particular, in the late Universe we measure a faster expansion and reduced clustering with respect to the expectations of ΛCDM from the measurements of the early Universe.

Although these tensions may be smoking guns for the need of physics beyond the standard cosmological model, they may also rise due to unaccounted for systematics in the observations or their analysis. Strikingly enough, nonetheless, there seems to be a trend in both cases, in which the tension arises between probes of the early and the late Universe. On the other hand, most of the models aiming to solve one of the tensions tend to worsen the other.

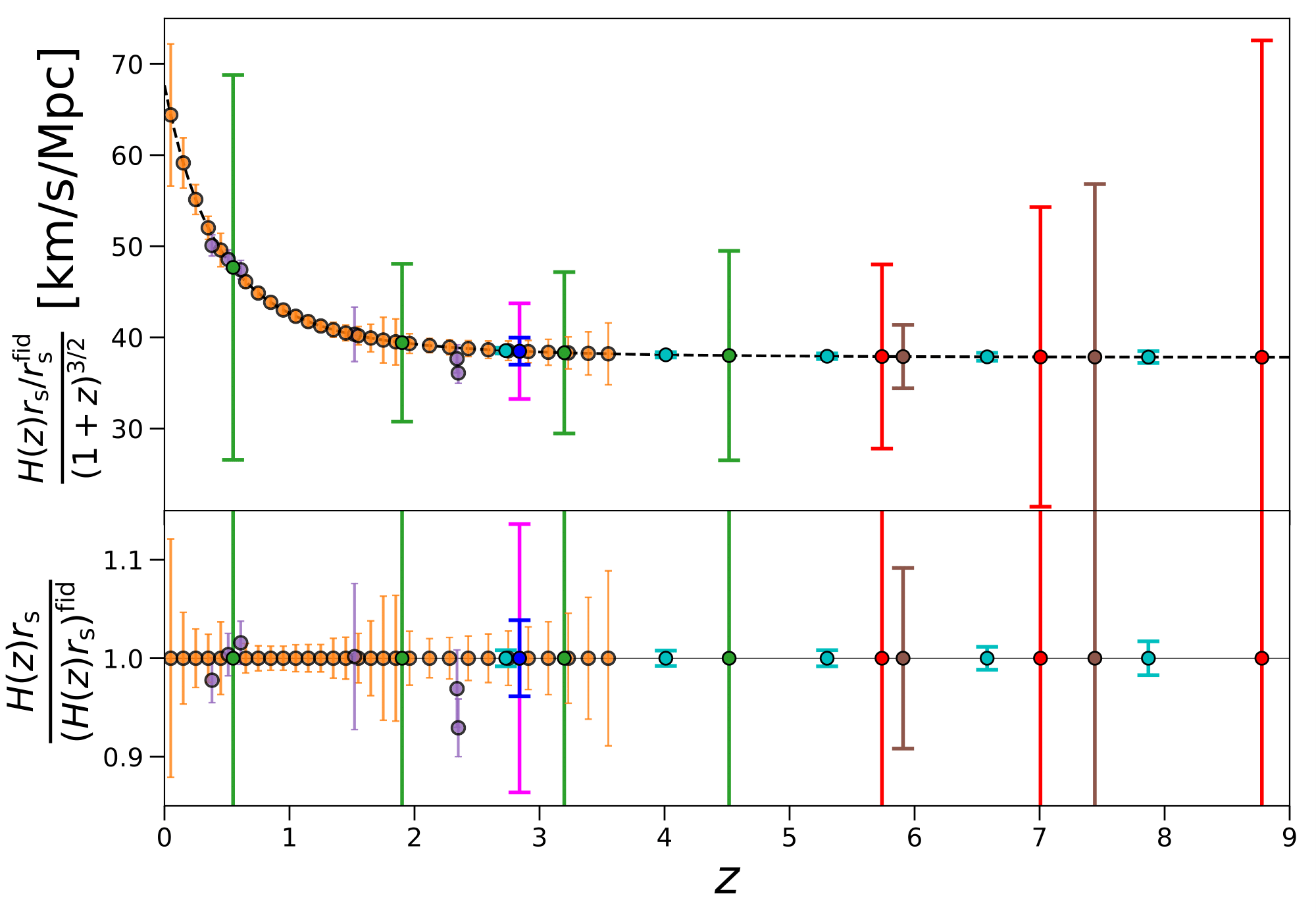

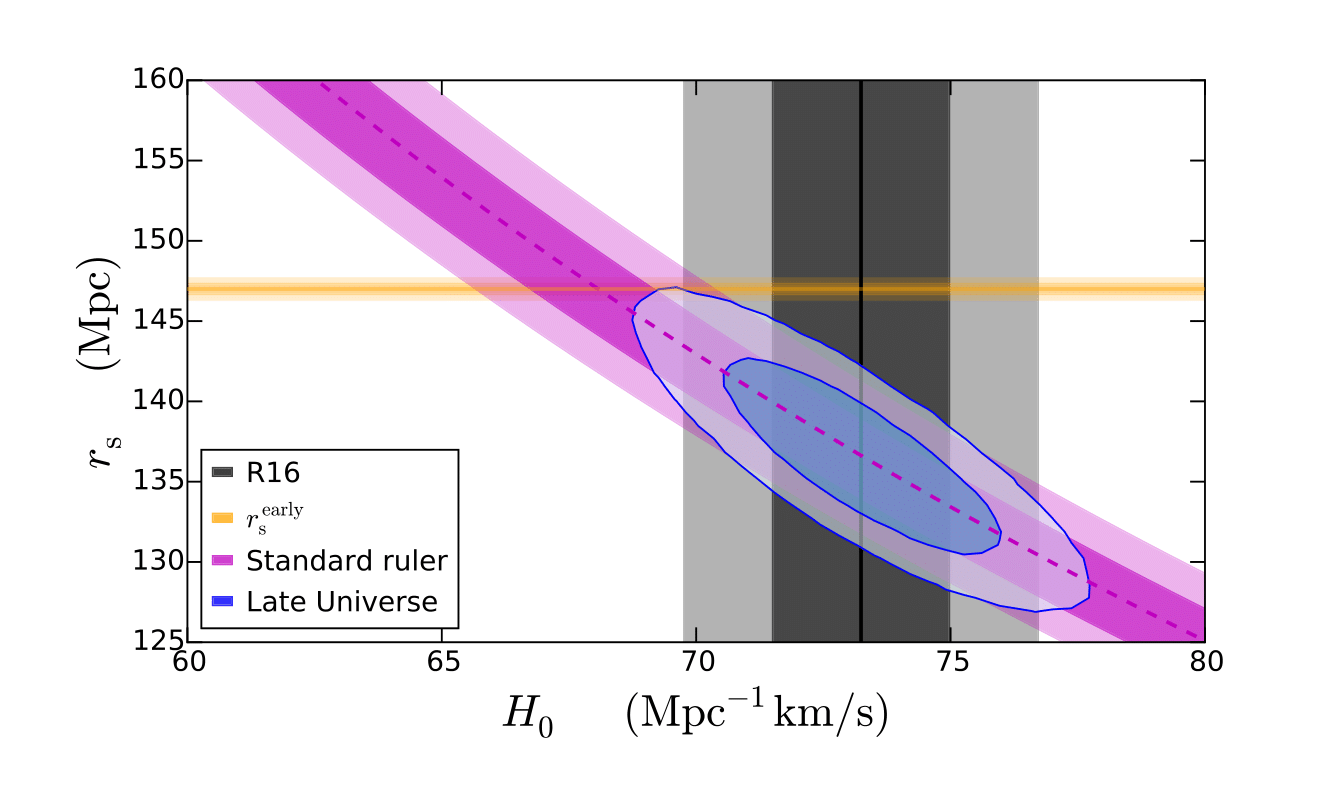

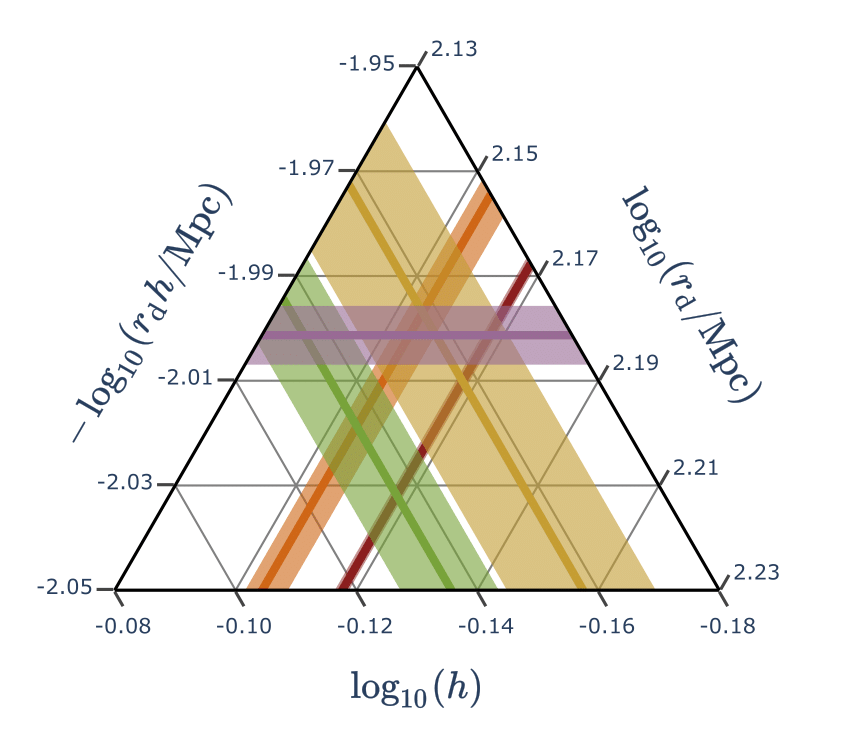

Most of my work regarding cosmological tensions has been on the Hubble constant tension, performing model-agnostic analyses (analyses with as-general-as-possible parametrizations, independent on any specific cosmologicla model) to find the features in the data that drive the tension. That way, I highlight that the tension can be reframed as a mismatch between the anchors of the direct distance ladder (H0), and the inverse distance ladder (which uses the sound horizon rd at radiation drag to calibrate the expansion history using BAO measurements), with their product very well constraint from BAO+SNeIa. This has led theoretical research, as the most promising models aiming to solve this tension depend on the reduction of rd to succeed. I have experience working with some of these models, such as early dark energy or hot QCD axions as additional relativistic particles in the early Universe.

No matter how exciting the perspective of physics beyond ΛCDM may be, systematic errors must be considered, both in the analysis of the observations and in the theoretical considerations of potential new physics explored. with that in mind, I have checked that the standard BAO measurements (which assume ΛCDM) are robust for models that modify the standard cosmological model before recombination, and I have developed a methodology to combine data sets and likelihoods to obtain conservative constraints, no matter the degree of tension between them.

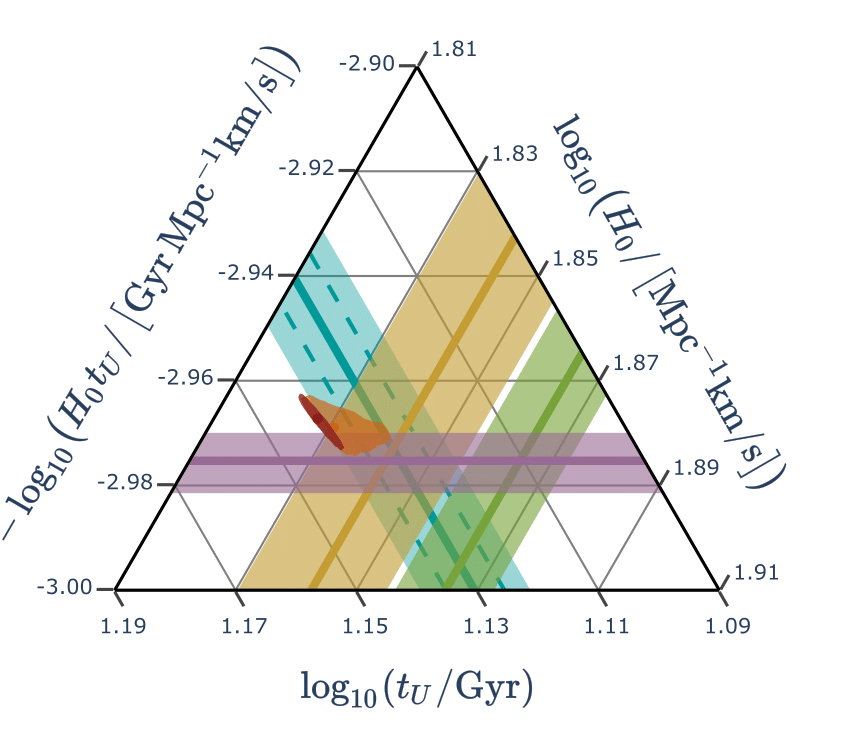

In addition, I have also collaborated with scientists from TDCOSMO in obtaining a more model-independent constraint on H0 from strong lensing time delays, and with the SH0ES team to obtain a measurement of H0 discarding SNeIa and using cepheids as the last step in the local distance ladder. Regarding alternative measurements of H0 or related quantities, I have collaborated in a novel analysis of globular clusters to infer the age of the oldest ones, and using it to infer the age of the Universe marginalizing over other cosmological parameters. Since the age of the Universe tU∼1/H0, this constraint informs potential solutions to the Hubble constant tension. Although current systematic errors limit this measurement, it hints to the need of modifying both the early and late Universe to reconcile all measurements.

I am starting to think now in the clustering tension, since there are more observations, probes and analyses focused on these quantities and the tension keeps growing. At the moment, I am exploring different models of interactions in the dark sector that may explain the reduced clustering in the late Universe with respect to the predictions from the evolution of the observed CMB.

Related talks:

- The trouble with H0 (and beyond) - Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics, KICP, UChicago - 2021.